|

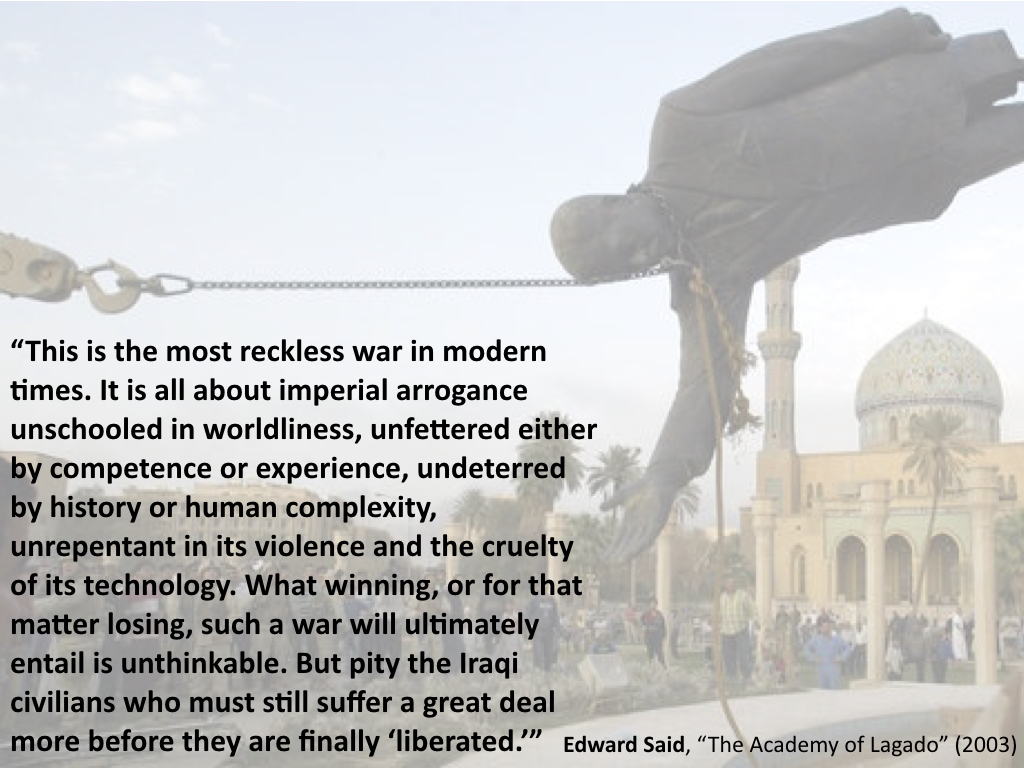

The publication of the Chilcot report earlier this week brought back lots of memories of the early 2000s. While there may have been none of the now daily political catastrophes that seem to be unfolding on my computer screen, these were dark days of political hubris, covert negotiations and war. This passage from the late literary critic Edward Said, in his LRB essay "The Academy of Lagado," cuts to the heart of the thinking of many at the time: Like the pointless experiments conducted at Jonathan Swift's Academy, UK and US political and military planners saw Iraq as an lab-like space on which to foist the unchecked visions of a fundamentalist President, a teflon Prime Minister and a woefully misinformed public.

Since the invasion of Iraq in 2003, more than 160,000 Iraqi civilians have died.

0 Comments

I received my first batch of marking this morning, so my reading and writing takes a (forced) step back over the next couple of weeks. I did manage to do some reading on the train to London this morning, and it was a real treat. I read Joseph Masco's "The Age of Fallout" in History of the Present and it ranks as one of the best papers I've read in a while. It is a wonderfully written account of the history of fallout, weaving a precautionary tale from the testing grounds of Nevada to modern nuclear accidents, via a discussion of geo-engineering and the securitisation of humans (or "breathers" as Timothy Choy notes). Craters from some of the 739 underground nuclear explosions on Yucca Flat, Nevada Test Site (Geekstroke) Here is how Masco (p. 158) summarises his argument through the eerily scarred and irradiated landscape (above) of the Nevada Test Site that was so central in the history of atomic weapons research:

"The (nuclear-petrochemical) industrial state has ... been geoengineering since 1945, remaking both atmospheres and ecologies, creating problems impossible to remediate or clean up. Today the Nevada Test Site contains valley after valley of radiating nuclear test craters—a monumentally changed environment only visible in its entirety from a stratospheric point of view. Here, industrial injury requires a new planetary vision, one that sees cumulative environmental effects over and against national boundaries, military science, or short-term profit making." In my final few days in Geneva, I managed to finish off Daniel Immerwahr's brilliant Thinking Small: The United States and the Lure of Community Development (Harvard, 2015). The book is a well-researched and exhaustively footnoted account of the rise and fall of "community development" thinking in international and US domestic policy. Like Nick Cullather and David Ekbladh before him, Immerwahr interrogates the close ties between modernisation and geopolitics in the early Cold War. There are the usual actors here (philanthropic foundations, the CIA, social scientists, agricultural consultants) and also a set of actors that are less familiar (the Black Panthers and Chinese literacy campaigners). But there are several things about this book that make me think it worth briefly expanding upon. The basic premise behind the book is that generations of scholars have approached modernisation as a hegemonic and monolithic project that swept away any alternatives and became the uncontested driver of US development interventions. In the era of damns and huge infrastructure projects, it is suggested that the world somehow "got bigger" - both in the size of the projects planned and also in terms of the geographical reach of US ambitions. Immerwahr, however, is unconvinced. He traces a series of communitarian counter-currents that were far from marginal during this period (although they are strangely silenced in accounts); this was the period "when small was big" to borrow from one of the chapter titles. In successive chapters, Immerwahr explores the disenchanted urban elites that fled big US cities in the early twentieth century; the management consultants that downsized factory teams to harness their increased efficiency; the village development models that were so popular with India's modernist-in-chief, Nehru; the strategic use of community organisations as a counter-insurgency platform in the Phillipines; and, ultimately, the return to the US of this community thinking as part of President Johnson's War on (Urban) Poverty. Modernisation and community development occurred side-by-side in this narrative; importantly, one did not eclipse the other. Post-war Washington was home to the modernisers (including Walt Rostow), but their agents in the field were the community-minded development officials. This, Immerwahr suggests, is one of the reasons why our extant accounts find modernisation everywhere - from the archives at the centre the path of modernisation seems uncontested. Communitarian views did not disqualify development consultants from a seat at the table of post-war development planning; rather, these counter-prevailing views were exactly why they were hired in the first place. Of course, there were failings of the community-focused initiatives, and that is why modernisation is ultimately considered to have "won out." In India, the community initiatives did not directly confront caste and gender systems that allowed even the best-laid plans to be co-opted by existing elites in a form of "backhanded authoritarianism" (94). Likewise in the Philippines, funding to community projects became yet another route for pork barrel money to flow from the political dynasties in the capital into the hands of local landed elites. I think it was the section on the US War on Poverty, though, that piqued my interest. The "discovery" of poverty in the richest country in the world raised serious questions for successive administrations in the late 50s until the 70s. Overseas community development became a training ground for action at home; indeed, a domestic version of the Peace Corps was considered the best plan for tackling rising urban decay and strife. "Having spent so much time busying itself with the economics of prosperity," Immerwahr writes (137-138), "the US government lacked domestic expertise in the area of persistent poverty [...] So just as the hydraulics of expertise had once pushed rural experts from the New Deal out to the global South to become community development experts, the discovery of domestic poverty reversed the flow and pulled foreign aid experts back to the United States as poverty warriors." This penultimate section of the book is the most interesting for me as it contends with this "reverse flow" of experts and ideas. But just as the limits of community development were reached in the Global South, so too were the US campaigns co-opted by others with differing visions of what community empowerment looked like (albeit from unlikely sources - Saul Alinsky, Jane Jacobs and the Black Panthers). Community didn't look like it did in the Global South and this challenged established orthodoxies, making many of the political backers of the campaign uneasy: Of course, this "cookie cutter" model of development failed. That was not the end of the story though, for the idea of community has a lasting allure as a catalyst for improvement. Immerwahr ends with some reflections on the future of community development, and these are pertinent for those of us interested in alternative models of development and the reimagining of our present. We are confronted by the necessity of hybrid arrangements as complex emergencies and development pathways demand new forms of collaboration and thinking from outside the box. The co-existence of modernisation and community thinking, exposed in Immerwahr's account, is a precursor of this. We must, unlike the community thinkers of the mid-twentieth century, avoid the implicit blaming of the poor for their situation; they have been "empowered," yes, but this is for nought in the absence of a broader critique of the structures that disempowered them in the first place. Likewise, for all of the talk of wanting to improve the well-being of distant communities, the securitisation of migration (as seen on the shores of the Mediterranean today) exposes the fact that our own prosperity is, to some extent, premised upon the exclusion of those who want access to wealth - the communities, in other words, need to stay put.

I finish with Immerwahr's closing words (184), as I think these are prescient, and a great overview of the book's key argument: "To recognize communitarianism's place in history is to give up on a fantasy, the fantasy that community is the great untried experiment of the industrial age. It is to treat community with less reverence and with more curiosity, to move it from the altar to the dissection table. Perhaps that is where it belongs. The problems of poverty are no less dire now than they were in the middle of the twentieth century. Solving them will require a clear-eyed understanding of what communities can do - and what they cannot." Those following along on Twitter will know that I've been in Geneva since Sunday 8th May. I'm working on the final stages of a British Academy/Leverhulme Trust funded project on the history and politics of disease eradication. This builds upon my earlier work on polio eradication, which was published in Geoforum earlier this year. In this particular project, I am interested in how the "pursuit of zero" is conceptualised, marshalled and evidenced in historical eradication campaigns. Last August, I returned to the Rockefeller Archive Center to examine the early twentieth-century campaigns against hookworm and yellow fever. In my second archive stint, I have been in the WHO archives this week looking at material relating to the ultimately successful "eradication" of smallpox (scare quotes used as samples do still exist in Russian and US bioweapons facilities). The rather imposing WHO headquarters, Geneva. The archives are in the basement. This time away from London has been very helpful in giving me some space to think through comparisons and contrasts that can be made between the work of Rockefeller and WHO (here I owe a debt to Anne-Emmanuelle Birn's work). I am reminded again of the significance of early health efforts in spreading the message of development and modernisation, and it is interesting to see similar sentiments expressed in the diaries of Rockefeller and WHO field operatives (some, as I have discovered, worked for both agencies). The plan is to write two larger papers on each of the organisations and a third piece that begins to craft a genealogy of eradication (something more conceptual than Nancy Leys Stepan's historical overview of the influential eradicationalist Fred Soper). I have already begun the first piece on Rockefeller (I am particularly interested in their hookworm work in the plantation economies of Sri Lanka), and I plan to spend some time this summer trawling through the >20GB of WHO material that I have collected this week. Later in the summer, I hope to begin putting together a larger grant application on the intertwining problems of eradication, elimination and emergence. So what did I actually do? On Monday, I had the privilege of sharing some of my preliminary thoughts from Rockefeller with a team of my former colleagues at WHO, about 50 in all. My title was "Let us spray" - one of many awful puns that I hope will see the light of day as paper titles in the not too distant future! I was primarily making the conceptual case for a history of eradication, using (futile) contemporary efforts to eliminate Zika-carrying mosquitos as a way into a broader discussion about the hope and hype of efforts at eradication. I was able to explore some of the similarities and differences between Zika and yellow fever campaigns, while also getting some very interesting insights from the audience into contemporary containment efforts and the use of "medical countermeasures" in the fight against infectious disease. Lots to take away and think through, for sure. "Let us spray": opening slide of my presentation on Monday (Credit: Matthew Twombly/NPR) My time in the WHO archives was also interesting in comparing the different organisations' approaches to archival material. The Rockefeller archive is situated in a palatial mansion on the outskirts of New York City, and their large team of knowledgeable staff marshal the boxes of primarily paper materials from archive shelf to desk. They also (now) have an excellent electronic finding aid that makes searching materials much more efficient - each box, for instance, has a lengthy itemised description of its contents. In contrast, the WHO team is much smaller - but likewise excellent - based in the basement of WHO headquarters, and one gets the feeling that the on-going nature of their work (every day new e-materials are made by WHO staff globally) places significant pressures on them. No doubt, academic researchers making requests for material do not help the matter either! Certain elements of their archive are entirely digitised, but the finding aids are still only paper-based (leading to something of an impasse in requesting material in advance). Luckily for me, the Smallpox Eradication Programme (SEP) is entirely digitised and I was able to take copies of the files but only after having discussed fair usage in Geneva. The files are available in PDF, although much of the voluminous material is yet to be fully explored by the team. As the files are much more recent than the material at Rockefeller, many are marked confidential (smallpox was eradicated in 1980, meaning many key actors are still alive).

Fortunately for me, I have been invited to participate in screening the files. Because I have so many (!), the WHO have asked me to identify any potentially sensitive or confidential material that I discover in the process of my research. This is not to gag me - I can still cite the material - but to use my close reading to flag any documents within the digitised files that may need more consideration or redaction before they are made available online in their entirety. I have been tasked with flagging evidence of individual patient records and information on vaccine composition/stability data, among other things. This is very exciting, and an interesting side-story to my research. It is also the first step in moving the digitised material into an online open-access repository. Some of the material that I have requested is already flagged as "confidential" and I will have to wait a couple of weeks to see if I am given access to these materials; the WHO is, of course, wary of releasing certain information that may alienate it's member nations. Aside from the research, I have had a lovely time in Geneva. This is the fourth time that I have been to the city, and I am always surprised at how tranquil the place is. It is a large and grand city, but one never feels rushed or squashed. I have also had the chance to visit some colleagues at the university for the first time. Prices are high, of course, and this time I decided to stay in an apart-hotel that has a small kitchen. It means I can save a little money on food bills and also avoid the field-work trap of routinely eating lots of rich food! Today (my final day), I am also doing some preparatory groundwork for a new MA module that will involve a short field-trip to the Geneva-based health and development institutions. I also need to pick up some Toblerone... This week I am in Geneva working on my British Academy/Leverhulme Trust funded project on the history of disease eradication. I'll share more on my findings in the archives of the Smallpox Eradication Programme at a later date. I must admit that, perhaps unsurprisingly, I have enjoyed the time away from classes and the early morning commute! I've also found myself having plenty of time to catch up on reading - the archive I am working at is only open 9am-12pm, 2-4pm! In my time away from the archive, I have frequently been found sunning myself in the squares of the old city. I have managed to finish a book that has been on my shelf for a while now: Grégoire Chamayou's excellent Drone Theory (Penguin, 2015). I have been following Chamayou's work for several years now - I discuss his Les corps vils (La Découverte, 2014) in a forthcoming paper - and this latest polemic has been discussed at length, most notably in a series of posts by Derek Gregory. As the length of Gregory's account testifies, there is a lot in here for geographers. And yet it was also refreshing to discover that Chamayou acknowledges a significant debt to geographers (Gregory, Stephen Graham, Alison Williams and others) in his theorisation of the spatial-sensitivities of late-modern warfare. This is a philosophical and genealogical account, that deftly weaves a compelling and critical narrative moving from the empirically-rich discussion of the kill-chain to the broader theorisation of political bodies and the repercussions of dronisation/automation for the theorisation of sovereignty, responsibility and care. It's a short and easily-accessible book, so I won't go into a blow-by-blow account of its strengths (please, go read it yourself) but I do want to draw attention to a brief paragraph that piqued my interest in which Chamayou justifies his method. Having made strange the recent shift to drone warfare, Chamayou poses the question: "what might the theorisation of a weapon signify?" (p. 14). Here, he draws on the work of philosopher Simone Weil to remind us that an ethical discussion of conflict cannot solely meditate on the ends of warfare ("is it just?"), but must also be attentive to the means through which war is waged. For Weil (1999, 174), "the very essence of the materialist method is that, in its examination of any human event whatever, it attaches much less importance to the ends pursued than to the consequences necessarily implied by the working out of the means employed." In other words, we should avoid fixating on the moralisation of violence and do something else: examine the means through which violence is meted out, and examine what is determined through the choice of these particular means (as opposed to other possibilities). As Chamayou suggests: Wonderful! This is a call to remember the ways in which political problems are rendered technical; it is a call to re-evaluate the socio-political impact of this "new" technology and to use that as a way to highlight the moral implications of these developments. While I'm not working on drones or human warfare, I do see similarities here with the manner in which the question of disease eradication (a war on nature, if you like) is approached through a moral language (the "farewell to harms") and ignores the productive avenues of inquiry that a focus on the technical means facilities - an approach that allows us to re-examine, and problematise, questions of public health and underdevelopment.

"Become a technician" is a wonderful place to start a polemical account: familiarise in order that you may problematise. A lot to think about over the course of my final few days here in Geneva! I've currently got fieldwork on the brain. I'm in the process of writing a 3,000-word reflection for my PGCAP course on a field class that I was a part of before Christmas. I'm also looking forward to hosting a group of teachers next week at the East London Geographical Association for a half-day session on conducting urban fieldwork (with my colleagues Kate Amis and Alastair Owens). In that session, we will discuss fieldwork design and also reflect a little on the position of fieldwork in the new A-level specifications. How, for instance, can teachers do cultural geography research in a way that is rigorous, relevant and not at all fuzzy?

It was great then to sit down to read some more Isabel Stengers last night. I've now moved on to look at her multi-volume work on Cosmopolitics. Contained in the second volume is a wonderful section comparing the experimental and field sciences. Andrew Barry in his recent piece on "the geographical canon" in the Journal of Historical Geography cites this passage and notes that "[Stengers] seeks to give a new sense of value to those ecologies of practice that address the contingency, path-dependency and complexity of the world outside of the purified domain of the laboratory" (2015, 90). This is great to hear as I place particular value on field research as a tool to disrupt our established regimes of practice. However, it is also a challenge for our teachers who are heading out into the field with their classes. There is the ever present danger that the results in the field won't really map onto the conceptual/modelling work already done in the classroom. While physical geographers can talk about error bars and standard deviation, it seems a little trickier to square contingency with cultural geography. We'll be unpacking how to deal with the unexpected in human geography fieldwork next week. I'm going to include a little Stengers in my presentation to the teachers, and I'm going to leave them with this challenge taken from Cosmopolitics (see the slide below): how do we inhabit the problematic tensions between what our textbook models require and what the field chooses to disclose? Answers on a postcard. Now that the bulk of lecture writing for the year is over, my commute to London becomes a little less frantic. I swap the Keynote software for the iPad and finally delve into some of the books and papers that I have been stockpiling over the past couple of months. My "to read" list is very long, but I triage the readings according to projects that I am working on at the moment - I find it best to read only those articles or books that are directly relevant to my current writing and research.

It was great, then, to turn to a book that has long been on my shelf: Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Isabelle Stengers' A History of Chemistry (Harvard, 1996). Here is the description from the publisher: From the earliest use of fire to forge iron tools to the medieval alchemists’ search for the philosopher’s stone, the secrets of the elements have been pursued by human civilization. But, as the authors of this concise history remind us, “disciplines like physics and chemistry have not existed since the beginning of time; they have been built up little by little, and that does not happen without difficulties.” Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Isabelle Stengers present chemistry as a science in search of an identity, or rather as a science whose identity has changed in response to its relation to society and to other disciplines. The authors—respected, prolific scholars in history and philosophy of science—have distilled their knowledge into an accessible work, free of jargon. They have written a book deeply enthusiastic about the conceptual, experimental, and technological complexities and challenges with which chemists have grappled over many centuries. Beginning with chemistry’s polymorphous beginnings, featuring many independent discoveries all over the globe, the narrative then moves to a discussion of chemistry’s niche in the eighteenth-century notion of Natural Philosophy and on to its nineteenth-century days as an exemplar of science as a means of reaching positive knowledge. The authors also address contentious issues of concern to contemporary scientists: whether chemistry has become a service science; whether its status has “declined” because its value lies in assisting the leading-edge research activities of molecular geneticists and materials scientists; or whether it is redefining its agenda. A History of Chemistry treats chemistry as a study whose subject matter, the nature and behavior of qualitatively different materials, remains constant, while the methods and disciplinary boundaries of the science constantly shift. I was drawn to the book because of the connections between chemistry and the pharmaceutical industry (expanded upon by Andrew Barry and others). I'm particularly interested in the scientific-social-economic relations through which chemicals emerge. Bensaude-Vincent and Stengers suggest that matter that emerges through the research and development process is transformed into "informed material" that is rich in information and saturated by relations (in the laboratory and beyond). I've taken lots of notes here that will be relevant for my second year course on biomedicine - I will be expanding and re-writing this next year - so hopefully there will be some space to delve into the laboratory with my class. In particular, I think the slide below will feature somewhere: This morning I received a copy of Guillaume Lachenal's Le medicament qui devait sauver l'Afrique (La Decouverte, 2014). The title is translated to English by the publishers as The hidden story of the medicine meant to save Africa. I've encountered Guillaume's work before, particularly his theorisation of colonial "absurdity" and unreason.

As it's going to take me a while to plough through the French text (I'm a little rusty) for a full review, here is the English overview of the text from the publisher instead: "The story, deliberately concealed, begins in the 1940s and continues until the 1970s. It is about a "miracle remedy for sleeping sickness" : Lomidine. Before being recognized as ineffective and dangerous, it was injected millions of times in Africa. The author follows its history step by step, showing the ways in which the medicine was used as a tool of power. A bitter, unprecedented historic investigation on the underside of colonial politics." For those that can't wait for my own review, you can read an excellent overview of the book by Pierre-Marie David at Somatosphere. |

Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed